Welcome to today’s post about understanding pieces produced verses value sold.

For our purposes today, production is defined as merchandise worked to the floor out of donations. This post assumes adequate quality donations are coming in.

In thrift production, most operations count pieces sent to the salesfloor. It’s a quick and easy way to keep track. Understanding pieces sold versus pieces produced is a good way to measure product flow.

Dollars go in the bank, not pieces.

Associating production to dollars sold can be next level. As mentioned in a previous post, there are POS systems that can help. I have used them, and they are a great if expensive investment.

Whatever the benchmark for producers, it’s important to keep in mind that it’s human nature for people to make the rules work in their favor. When success is strictly measured by pieces, you get a lot of pieces. Producing value can become secondary.

I have seen producers ticket 100 CD jewel cases for fifty cents each and mark that as production. Technically correct as the measure is in pieces. Unfortunately, the value produced was negligible.

So if you see jewel cases, too many paperback books, silverware, out of season clothing counted as production, well, those are the rules.

Even without a fancy POS system, it is possible to encourage teams to understand their impact on prices at the cash register.

Keeping track of the ticketed value of each item produced by hand is unwieldy and may or may not relate to the value sold.

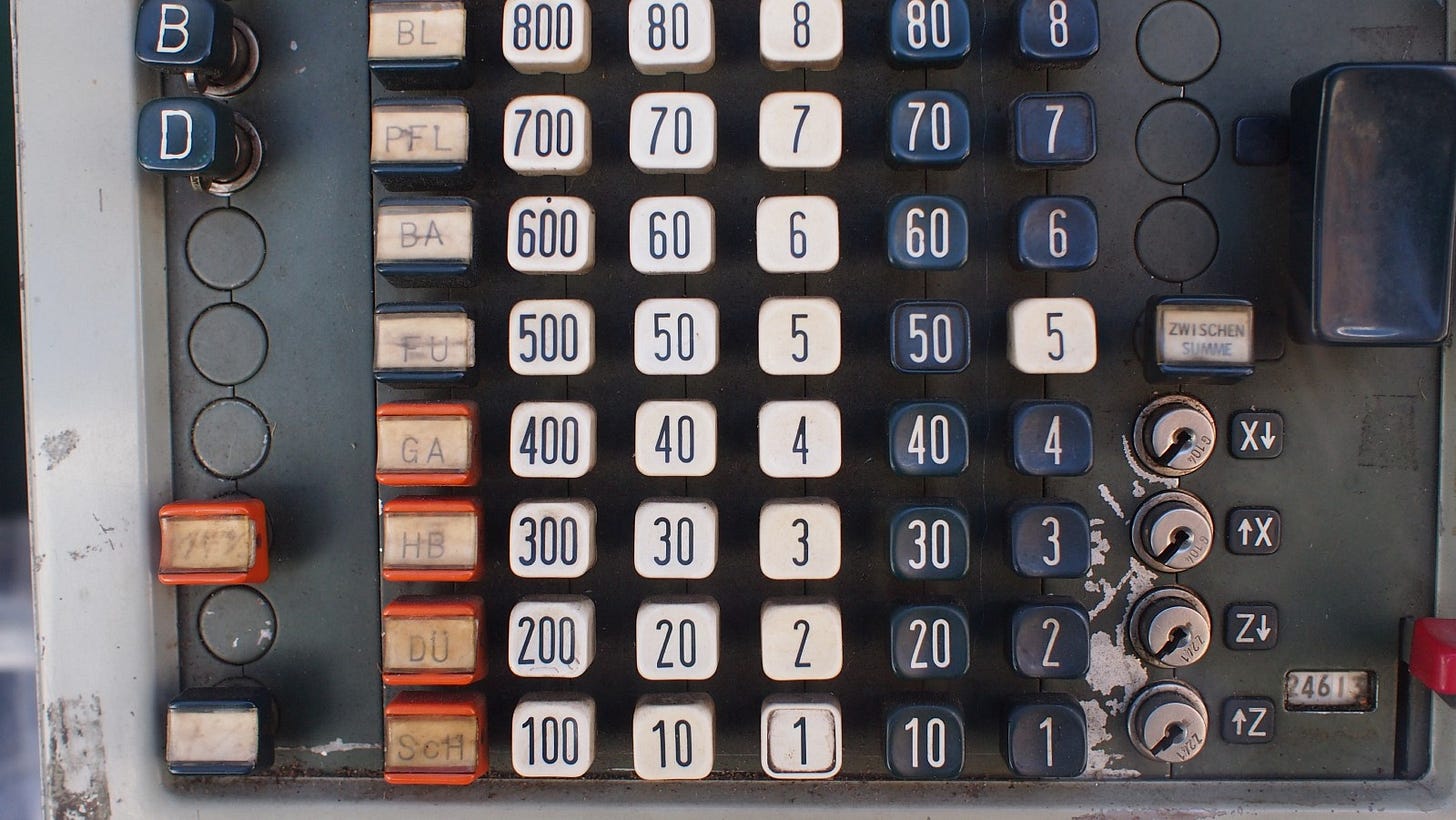

Winning in business and life is often about doing what you can with what you have. So what to do with a basic cash register?

Even the most basic register gives items and dollars sold by the department. A little simple division gets you to an average price per item.

Dollars sold divided by pieces sold, equals average price per item sold.

Tracking all three of those data points across time makes them valuable. Weeks, months, quarters, and years can be very telling. Categories with rack or set pricing are the easiest to understand.

Watching the ebb and flow of pieces sold can be telling. The simple trick is to ask why? Was there a jump, or drop, because of a great or terrible production week, a new staff member, or a holiday? It can also help you see the results of changes in the store, from floor layout moves to price moves to promotional changes.

The average price per item sold is a key measure that we will focus on in this post.

Move prices up too much and pieces sold drop. Sell stuff too cheap and production has to be raised without enough revenue to justify it.

It takes about the same amount of labor to price something for $1 as $5, or even often $50.

There is a balance between the price per piece and the pieces sold. There is a sweet spot. It’s a little different for each market.

Let’s say Women’s tops are a register category that is rack priced at $5.99. In a perfect world, the average price per item through the register would be 5 99. Not really, more on why that’s bad later.

A great way to measure how well you are doing is to track the spread. If those women’s tops have an average actual sell price of $4.58 your production versus sell price spread is -$1.41. That’s without accounting for goods that do not sell and are rejected or ragged. Maybe another post.

The trick is to understand what drives the spread.

The biggest mover is the percentage that hits the color mark down rotation. Zero isn’t the right answer, but neither is two thirds.

I am fond of Brooks Brothers button-down dress shirts. As niche as that brand is I still find them while thrift shopping. Almost every time they are priced the same as big box brands like Faded Glory.

That is the most common issue, too many low-quality goods for sale and high-quality goods not priced to their value.

Faded Glory and their basic brand cousins will often sit around until it hits the color discount rotation. The first time someone that knows what a Brooks Brothers shirt is that is in the right size, it’s sold.

I once experimented with a store with more than abundant donations. We quit putting big box basic brands on the sales floor at all. They were sent to the outlet or a store that wasn’t getting enough donations. Textile sales went up, the average price per item went up, and sell-through went up — all wins.

There are plenty of places that wouldn’t work but it showed the value of a focus on quality.

Quality is the single biggest driver.

Auditing say 100 pieces on the floor can be very telling.

Some textile things to look for:

stains, rips, tares

out of season

dated, unpopular styles

buttons missing

holes

taggers not in seams

cheap brands

Textile producers should be rejecting things with these issues before they get to the sales floor. A few will always get through, 95% acceptable is a good benchmark.

Pro tip: On store tours randomly pull out items and look them over.

A best practice is to have someone in leadership verify counts and spot-check goods before they get to the sales floor.

Setting, training to, and regularly verifying quality expectations keeps that spread down.

Second is merchandising. During that same audit, are sizes organized? Are smalls in the smalls section and so on? Are size differentiations easy for customers to identify? That beautiful XL top in the smalls section isn’t going to find a new home.

The same is true of stereo speakers in the toy department, office supplies in the craft department, and so on. Merchandise organization is just as important in thrift as in traditional retail.

Good merchandising increases sell-through.

Sometimes production is too high compared to customer traffic. In those cases, quality goods aren’t exposed to enough potential buyers. Understanding production needed to support budgeted sales is an important component of a properly managed thrift operation, and a bit much for today’s post.

Sometimes the rack price is too high. That is seldom the case, which is why it’s important to eliminate product, merchandising, and production issues first.

Consistently selling nearly everything at full price isn’t necessarily a win. It can mean the rack price is lower than it needs to be. A price increase might be in order.

. . . .

A good way to more fairly capture value is to use a good/better/best pricing strategy. Big box basics are priced lower as good, most items are priced better, then really nice things best. A couple dollar-ish spread between each can move the needle at the cash register.

With my Brooks Brothers example, I would happily pay a few more dollars to purchase those in a thrift store. But I am not asked.

. . . . .

The goal isn’t 100% sell-through of everything on the sales floor. Being too picky results in too many good items being rejected and sent to salvage without a chance to sell.

This process works great with every category that is recorded separately at the cash register which also has fixed pricing.

Even without fixed pricing, watching department trends over time is telling.

In my ReStore world furniture is an important department. Prices vary greatly, sometimes our best item is $100, and sometimes it’s $1,000. Because of that, the average price per item doesn’t mean much in a day or even a week. Months seem to average out. So we watch trends over the months.

Accountability moves numbers.

People want to know how they are doing. It is also human nature, so keep score. Everyone should know what the goals and expectations are for every tracked category and the store overall.

In my opinion, dry-erase boards are one of the greatest inventions of all time and are excellent communication tools.

Posting daily and weekly results versus goals gets the staff directly involved in success. If there is a bad production day because of call-offs or whatever, it’s easy to work with staff to figure out how to catch up.

In conclusion:

Know your numbers, know why those are the numbers, and over-communicate how things are going.

Involve everyone in solutions. Staff usually know better than management why things are going like they are.